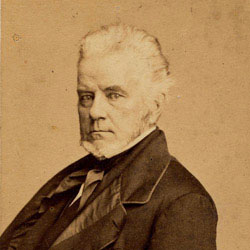

Lowell Mason

Lowell Mason

&

The"Better Music" Boys

Excerpt from A Short Shaped-Note Singing

History

By Keith Willard

The singing school, a vigorous social institution developed in the

English parish country side, was continued in eighteenth century New England. Invented in part to improve the quality of congregational singing, the singing school soon outstripped its purely church-centered focus and became an integral part of the social life of the community. Held for a week or month at a time, itinerant singing school masters would teach both secular and sacred three- and four-part music to a room filled with energetic colonial young adults of both sexes.

These singing masters frequently became their own tunesmiths, cranking out lively pieces, arranged in harmonies that emphasized polyphonic rather than vertical harmonic lines. Instead of composing in conformance with rigid European conservatory "rules" of the times, tunesmiths such as William Billings, Daniel Read, and Justin Morgan used as models the vigorous Scottish and English parish church psalmody which made free use of counterpoint and dance rhythms coupled with loose harmonic rules.

In New England, the singing school institution flowered briefly in the period prior to the Revolutionary war but then faded. A post war influx of European style trained musicians, systematically campaigned for the removal of this "crude and lewd" music and its schools. Under the influence of Lowell Mason and like ilk, the teaching of singing moved from the informal process of community singing schools to the rigid (and regulated) control of the public schools. The "Better Music Movement" was largely successful in the cities of the NorthExcerpt from the

Recorded Anthology of American Music, Inc.,

liner notes, commenting on Lowell Mason......

Lowell Mason was the latter-day chief of the "scientific" Better Music movement that drove the popular shape-note tune books of the old Yankee singing masters out of New England, leaving what used to be called the Old Southwest (then not including Texas) the only spirited congregational singing in the country to this day, and bequeathing the Protestant Church in the Atlantic states its long, sad heritage of hired soloists, paid choirs, and shamefaced congregational mumbling. Not in the more than twelve hundred hymns with which Mason denatured our acts of communal praise nor in the pious secular inanities he pumped into our public-school music books is there a trace of our antecedent musical history or our native musical vitality. His hymns are so dully correct in harmony, so feeble in melody, and so uniform in their watery characterlessness that they constitute a monument to Christian antimusicality. At length one realizes that there is one function in which they are superb. Mason's hymns, like Charles Grobe's piano pieces, are marvelous commodities. Mason in fact packaged hymns as others packaged beans or cod, and there is evidence that he was not above exploiting a monopoly situation in the hymn and schoolbook markets.

Excerpt from the writings of "The Community Band of Brevard"

The combination of the solfege singing system and the shaped note printing system fostered the popularity and wide spread of social singing events in America. However, the "Better Music Movement" led by Lowell Mason in the early nineteenth century pushed for the removal of this "crude and lewd" music. Mason's movement was successful except in the rural South (regions of Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Texas).

George Pullen Jackson, an early 20th-century shape-note music scholar, lumped Mason and the other critics together as the "Better Music boys" and rued their influence as they moved west in the 1830s and 40s

(White Spirituals 16-19).

| So

there you have it...... Lowell Mason and his "better music" boys

were responsible for a wave of music censorship that forced

the music of our earliest American composers out of establishment

music circles, out of school music courses, out of churches

and into the world of "shape

note" singing, where it was preserved and saved from

the censorship of Mason and his ilk. The "better music" boys did manage to create a situation where the music of our first American composers remained almost unknown, even in most University music programs. Until the 20th Century that is...... when the modern wave of American composers rediscovered this music and it once again saw the light of day. |

Back to the William Billings page

Early American music,

unusual & unique music,

and ephemera collection.

Explore - The Amaranth Publishing links to the world's most mysterious book, The People's Conspiracy, the world's oldest song, the music of the spheres,

the music of the Illuminati, the world's oldest love song, the 19th Century American X-files, a way you can compose music like Mozart,

and much more........