Oxyrhynchus

is an archaeological site in Egypt, one of the most important ever

discovered. For the past century the area around Oxyrhynchus has

been continuously excavated, yielding an enormous collection of

papyrus texts from the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods

of Egyptian history.

Oxyrhynchus

is an archaeological site in Egypt, one of the most important ever

discovered. For the past century the area around Oxyrhynchus has

been continuously excavated, yielding an enormous collection of

papyrus texts from the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods

of Egyptian history.

We know more about Oxyrhynchus as a city, and about its people as

living individuals, than we do about many more glamorous and famous

historic ruins because because of one thing: the town garbage dumps.

These remained intact right up to the late nineteenth century, as

they were not considered likely sites for treasure-hunters. They

have yielded the largest collection of ancient papyrus ever discovered.

Among the texts discovered at Oxyrhynchus are plays of Menander

and the Gospel of Thomas (an important early Christian document),

and the oldest known music notation and lyrics of a

Christian hymn.

The

Greek language flourished in Egypt for a thousand years. It first

began to be widely spoken there when the country was conquered by

Alexander the Great, who founded Alexandria in 331 B.C. and then

set off to extend his empire in the East.

The

Greek language flourished in Egypt for a thousand years. It first

began to be widely spoken there when the country was conquered by

Alexander the Great, who founded Alexandria in 331 B.C. and then

set off to extend his empire in the East.

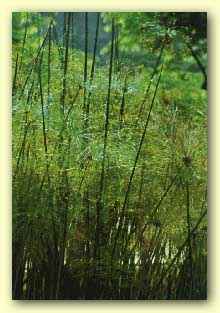

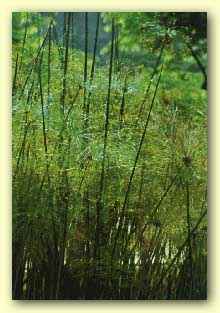

For

all this time in every part of the Greek-speaking world books and

documents were written on a paper made from the papyrus

reed, which was rare outside Egypt, and even there died

out in about the tenth century A.D. It is now to be found chiefly

in the Sudd, a vast area of swamp in the Sudan covered with thickets

of papyrus.

For

all this time in every part of the Greek-speaking world books and

documents were written on a paper made from the papyrus

reed, which was rare outside Egypt, and even there died

out in about the tenth century A.D. It is now to be found chiefly

in the Sudd, a vast area of swamp in the Sudan covered with thickets

of papyrus.

In Hellenistic times Oxyrhynchus was a prosperous regional capital,

the third largest city in Egypt. After Egypt was converted to Christianity,

it was famous for its many churches and monasteries. It remained

a prominent, though gradually declining, town in the Roman and Byzantine

periods. After the Arab conquest of Egypt in 641, the canal system

on which the town depended was allowed to fall into disrepair, and

Oxyrhynchus was abandoned. Today the town of el-Bahnasa occupies

part of the ancient site.

For

a thousand years the inhabitants of Oxyrhynchus dumped their rubbish

at a series of sites out in the desert sands beyond the town limits.

The fact that the town was built on a canal rather than on the Nile

itself was important, because this meant that the area did not flood

every year with the rising of the river, as did the districts along

the riverbank. When the canals dried up, the water table fell and

never rose again. The area west of the Nile has virtually no rain,

so the rubbish dumps of Oxyrhynchus were gradually covered with

sand and lay, dry, sterile and forgotten, for another thousand years.

For

a thousand years the inhabitants of Oxyrhynchus dumped their rubbish

at a series of sites out in the desert sands beyond the town limits.

The fact that the town was built on a canal rather than on the Nile

itself was important, because this meant that the area did not flood

every year with the rising of the river, as did the districts along

the riverbank. When the canals dried up, the water table fell and

never rose again. The area west of the Nile has virtually no rain,

so the rubbish dumps of Oxyrhynchus were gradually covered with

sand and lay, dry, sterile and forgotten, for another thousand years.

Because Egyptian society under the Greeks and Romans was governed

bureaucratically, and because Oxyrhynchus was a regional capital,

the material at the Oxyrhynchus dumps included vast amounts of paper.

Accounts, tax returns, census material, invoices, receipts, correspondence

on administrative, military, religious, economic and political matters,

certificates and licenses of all kinds — all these were periodically

cleaned out of government offices, put in wicker baskets, and dumped

out in the desert. Private citizens added their own piles of unwanted

paper. Because papyrus was expensive, paper was often re-used: a

document might have farm accounts on one side, and a schoolboy's

text of Homer on the other. The Oxyrhynchus papyri thus contained

a complete record of the life of the town, and of the civilizations

of which the town was a part.

The recovery of papyri began in the middle of the eighteenth century,

when the remains of a Greek library on papyrus rolls were found

in Italy at Herculaneum, preserved by the debris of an eruption

of Vesuvius. By the end of the eighteenth century a few papyri had

been discovered in Egypt, the country whose dry climate is most

favorable to their survival, and the number slowly grew. By the

eighteen-nineties exciting finds of Greek literature, lost works

by such authors as Aristotle and Hyperides, encouraged the Egypt

Exploration Fund (later Society) to commission excavations specifically

in search of papyri. In their second season, in 1896/7, B. P. Grenfell

and A. S. Hunt, two young fellows of Queen’s College, Oxford,

found the site that was to produce the largest collection of all

— Oxyrhynchus.

including the music of the spheres, the music of a Renaissance alchemist, music created by software and artificial intelligence, the music of the fairies, the music of the Illuminati, the world's most mysterious book, the world's oldest song, a way you can compose music like Mozart, the world's oldest love song,

The

Greek language flourished in Egypt for a thousand years. It first

began to be widely spoken there when the country was conquered by

Alexander the Great, who founded Alexandria in 331 B.C. and then

set off to extend his empire in the East.

The

Greek language flourished in Egypt for a thousand years. It first

began to be widely spoken there when the country was conquered by

Alexander the Great, who founded Alexandria in 331 B.C. and then

set off to extend his empire in the East.  For

all this time in every part of the Greek-speaking world books and

documents were written on a paper made from the papyrus

reed, which was rare outside Egypt, and even there died

out in about the tenth century A.D. It is now to be found chiefly

in the Sudd, a vast area of swamp in the Sudan covered with thickets

of papyrus.

For

all this time in every part of the Greek-speaking world books and

documents were written on a paper made from the papyrus

reed, which was rare outside Egypt, and even there died

out in about the tenth century A.D. It is now to be found chiefly

in the Sudd, a vast area of swamp in the Sudan covered with thickets

of papyrus. For

a thousand years the inhabitants of Oxyrhynchus dumped their rubbish

at a series of sites out in the desert sands beyond the town limits.

The fact that the town was built on a canal rather than on the Nile

itself was important, because this meant that the area did not flood

every year with the rising of the river, as did the districts along

the riverbank. When the canals dried up, the water table fell and

never rose again. The area west of the Nile has virtually no rain,

so the rubbish dumps of Oxyrhynchus were gradually covered with

sand and lay, dry, sterile and forgotten, for another thousand years.

For

a thousand years the inhabitants of Oxyrhynchus dumped their rubbish

at a series of sites out in the desert sands beyond the town limits.

The fact that the town was built on a canal rather than on the Nile

itself was important, because this meant that the area did not flood

every year with the rising of the river, as did the districts along

the riverbank. When the canals dried up, the water table fell and

never rose again. The area west of the Nile has virtually no rain,

so the rubbish dumps of Oxyrhynchus were gradually covered with

sand and lay, dry, sterile and forgotten, for another thousand years.