Jack Kerouac's Imaginary Baseball Game

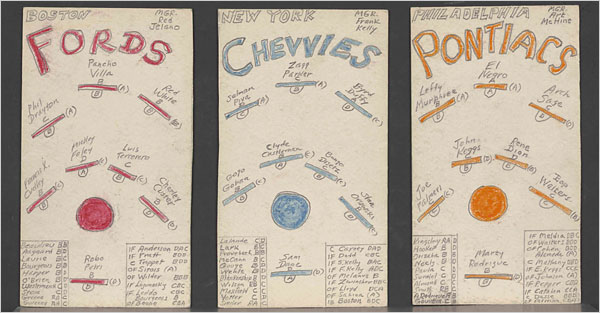

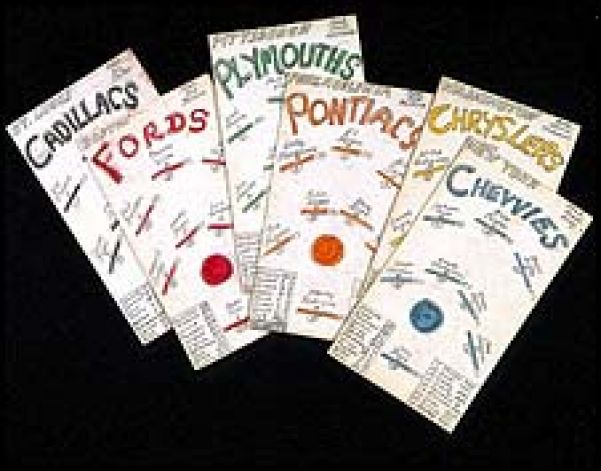

Almost all his life Jack Kerouac had a hobby that even close friends and fellow Beats like Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs never knew about. He obsessively played a fantasy baseball game of his own invention, charting the exploits of made-up players like Wino Love, Warby Pepper, Heinie Twiett, Phegus Cody and Zagg Parker, who toiled on imaginary teams named either for cars (the Pittsburgh Plymouths and New York Chevvies, for example) or for colors (the Boston Grays and Cincinnati Blacks).

Almost all his life Jack Kerouac had a hobby that even close friends and fellow Beats like Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs never knew about. He obsessively played a fantasy baseball game of his own invention, charting the exploits of made-up players like Wino Love, Warby Pepper, Heinie Twiett, Phegus Cody and Zagg Parker, who toiled on imaginary teams named either for cars (the Pittsburgh Plymouths and New York Chevvies, for example) or for colors (the Boston Grays and Cincinnati Blacks).

He collected their stats, analyzed their performances and, as a teenager, when he played most ardently, wrote about them in homemade newsletters and broadsides. He even covered financial news and imaginary contract disputes. During those same teenage years, he also ran a fantasy horse-racing circuit, complete with illustrated tout sheets and racing reports. He created imaginary owners, imaginary jockeys, imaginary track conditions.

All these “publications,” some typed, some handwritten and often pasted into old-fashioned composition notebooks, are now part of the Jack Kerouac Archive at the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library. The curator, Isaac Gewirtz, has just written a 75-page book about them, “Kerouac at Bat: Fantasy Sports and the King of the Beats,” to be published next week by the library and available, at least for now, only in its gift shop.

Mr. Gewirtz said recently that he had included much of the fantasy material in a 2007 Kerouac exhibition he mounted at the library, and had planned to add a chapter about the fantasy sports in the catalogue but ran out of space. “I’m glad I waited,” he said, “because it forced me to go into it all in much more depth.”

Among other things, Mr. Gewirtz has learned that Kerouac played an early version of the  baseball game in his backyard in Lowell, Mass., hitting a marble with a nail, or possibly a toothpick, and noting where it landed. By 1946, when Kerouac was 24, he had devised a set of cards with precise verbal descriptions of various outcomes (“slow roller to ss,” for example), depending on the skill levels of the pitcher and batter. The game could be played using cards alone, but Mr. Gewirtz thinks that more often Kerouac determined the result of a pitch by tossing some sort of projectile at a diagramed chart on the wall. In 1956 he switched to a new set of cards, which used hieroglyphic symbols instead of descriptions. Carefully preserved inside plastic folders at the library, they now look as mysterious as runes.

baseball game in his backyard in Lowell, Mass., hitting a marble with a nail, or possibly a toothpick, and noting where it landed. By 1946, when Kerouac was 24, he had devised a set of cards with precise verbal descriptions of various outcomes (“slow roller to ss,” for example), depending on the skill levels of the pitcher and batter. The game could be played using cards alone, but Mr. Gewirtz thinks that more often Kerouac determined the result of a pitch by tossing some sort of projectile at a diagramed chart on the wall. In 1956 he switched to a new set of cards, which used hieroglyphic symbols instead of descriptions. Carefully preserved inside plastic folders at the library, they now look as mysterious as runes.

The horse-racing game was played by rolling marbles and a silver ball bearing down a tilted Parcheesi board, using a starting gate made of toothpicks. Apparently, the ball bearing traveled faster than the marbles, some of which were intentionally nicked to indicate equine fragility and mortality. So the ball bearing became the nearly invincible horse Repulsion, “King of the Turf,” whose legendary speed and stamina are celebrated in Kerouac’s racing sheets.

A byline that frequently appears in the racing sheets and the baseball newsletters is “Jack Lewis,” an Anglicization of Kerouac’s French first name, Jean-Louis. Jack Lewis, you learn from a careful reading of the sheets, is also a “noted turf luminary,” an owner and trainer who happens to be married to a wealthy breeder and whose 15-year-old son, Tad, is “expected to become a greater jockey than his immortal dad.” In baseball, Jack Lewis is a scribe and the publisher of Jack Lewis’s Baseball Chatter, and he appears occasionally both as a player and a manager.

A byline that frequently appears in the racing sheets and the baseball newsletters is “Jack Lewis,” an Anglicization of Kerouac’s French first name, Jean-Louis. Jack Lewis, you learn from a careful reading of the sheets, is also a “noted turf luminary,” an owner and trainer who happens to be married to a wealthy breeder and whose 15-year-old son, Tad, is “expected to become a greater jockey than his immortal dad.” In baseball, Jack Lewis is a scribe and the publisher of Jack Lewis’s Baseball Chatter, and he appears occasionally both as a player and a manager.

That Kerouac, growing up in Lowell in the 1920s and ’30s, would turn out to be sports-obsessed is not much of a surprise. His father was a serious racing fan who for a while supplemented his income by printing racing forms for local tracks. Kerouac himself was a good enough athlete to be recruited by Frank Leahy, then the football coach at Boston College. He picked Columbia instead, because he was already dreaming of becoming a writer and thought New York was the place to start.

And that Kerouac had an active fantasy life hardly distinguishes him from other teenage boys. What’s remarkable about his fantasy games, however, is their elaborateness and detail. The players all have distinct histories and personalities. A single season could last 40 or 50 games, with an All-Star game and a World Series, all painstakingly documented.

In an introduction to “Kerouac at Bat,” Mr. Gewirtz suggests that Kerouac was trying, in part, to escape the pain and confusion he suffered from the death of his older brother, Gerard, when Gerard was 9 and Kerouac just 4. But whether he knew it or not, the creation and documentation of fantasy worlds were ideal training for a would-be author.

The prose in Kerouac’s various publications mostly imitates the overheated, epithet-studded sportswriting of the day. “It was partly homage,” Mr. Gewirtz said, “and perhaps partly parody, but every now and then an original phrase leaps out.” For example, the description of a hitter who “almost drove Charley Fiskell, Boston’s hot corner man, into a shambled heap in the last game with his sizzling drives through the grass.”

Mr. Gewirtz said, “I really like that ‘shambled heap.’ ” Another description he enjoys is one of an overpowering pitcher who after defeating the opposition by a lopsided score “smiled wanly.”

Kerouac wrote his last baseball account, two mock United Press International reports, in 1958, but he continued to play the game and to tinker with its formulas, making them more realistic, until just a year or two before his death in 1969. His friend the poet Philip Whalen was probably the only one of the Beats who was familiar with this side of Kerouac.

“I don’t think the others knew,” Mr. Gewirtz said. “Or if they did, they didn’t learn it from Kerouac. I think he was worried they might think it childish.” But in Mr. Gewirtz’s view Kerouac’s interest in playing and writing about this self-contained imaginary world goes a long way toward dispelling the familiar criticism of him as less a writer than a sort of inspired typist.

“I think Kerouac had a photographic memory — a visual photographic memory,” he said. “These games were real to him: he saw them in his head, where he was able to store everything. To me it’s another indication of the kind of mind that allowed him to be the writer he was.”